This is an edition of The Atlantic Daily, a newsletter that guides you through the biggest stories of the day, helps you discover new ideas, and recommends the best in culture. Sign up for it here.

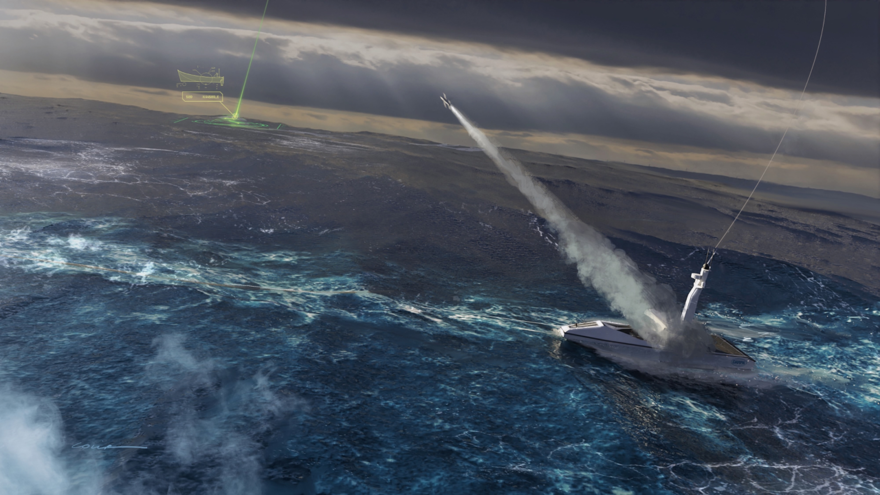

Earlier this week, Secretary of Defense Pete Hegseth sat down with Dario Amodei, the CEO of the leading AI firm Anthropic, for a conversation about ethics. The Pentagon had been using the company’s flagship product, Claude, for months as part of a $200 million contract—the AI had even reportedly played a role in the January mission to capture Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro—but Hegseth wasn’t satisfied. There were certain things Claude just wouldn’t do.

That’s because Anthropic had instilled in it certain restrictions. The Pentagon’s version of Claude could not be used to facilitate the mass surveillance of Americans, nor could it be used in fully autonomous weaponry—situations where computers, rather than humans, make the final decision about whom to kill. According to a source familiar with this week’s meeting, Hegseth made clear that if Anthropic did not eliminate those two guardrails by Friday afternoon, two things could happen: The Department of Defense could use the Defense Production Act, a Cold War–era law, to essentially commandeer a more permissive iteration of the AI, or it could label Anthropic a “supply-chain risk,” meaning that anyone doing business with the U.S. military would be forbidden from associating with the company. (This penalty is typically reserved for foreign firms such as China’s Huawei and ZTE.)

This evening, Anthropic said in a public statement that it “cannot in good conscience accede” to the Pentagon’s request. What happens next could mark a crucial moment for the company, and for the American government’s approach to AI regulation more broadly. In refusing to bow to an administration that has been intent on bullying private companies into submission, Amodei and his team are taking a bold stand on ethical grounds, and risking a censure that could erode Anthropic’s long-term viability.

During the first year of Donald Trump’s second term, the White House had a more relaxed attitude toward AI regulation; an AI Action Plan from July stresses that the administration will “continue to reject radical climate dogma and bureaucratic red tape” to encourage innovation. Hegseth is now, in effect, threatening to partially nationalize one of the biggest AI players in the private sector—and force the company to go against its own principles. “This is the most aggressive AI regulatory move I have ever seen, by any government anywhere in the world,” Dean Ball, who helped write some of the Trump administration’s AI policies, told me.

The Pentagon has already reportedly been reaching out to other defense contractors to see if they’re connected to Anthropic, a sign that officials are preparing to designate the company a supply-chain risk. Now that Anthropic has defied Hegseth, the contract is likely in peril. The firm doesn’t really need the $200 million—it reportedly pulls in $14 billion a year, and it said it raised $30 billion in venture capital just weeks ago—but being blacklisted could affect its ability to scale up in the future. (“We are not walking away from negotiations,” an Anthropic spokesperson told The Atlantic in a statement. “We continue to engage in good faith with the Department on a way forward.” The Pentagon told CBS on Tuesday that “this has nothing to do with mass surveillance and autonomous weapons being used,” and that ”the Pentagon has only given out lawful orders.”)

As AI firms around the world jockey for dominance, Anthropic has distinguished itself by emphasizing safety. OpenAI’s ChatGPT has been criticized for playing up some users’ delusions, leading to cases of “AI psychosis,” and just last month, xAI’s Grok was spinning up nearly nude images of almost anyone without consent. (xAI has said it is restricting Grok from generating these kinds of images, and OpenAI has said it is working to make ChatGPT better support people in distress.) Meanwhile, Anthropic’s consumer-facing chatbot doesn’t generate images at all. By refusing to cave to government pressure, it may have just averted another crisis: a major public backlash from consumers, some of whom see the company as a more principled player in the AI wars. Anthropic recently faced some pushback over changing its policies—Time reported on Tuesday that, in a seemingly unrelated move, the company dropped a core safety pledge concerning its broader approach to AI development.

Weeks before Hegseth issued his ultimatum, Amodei opined on his website about the risks involved with precisely the two guardrails the Pentagon is targeting. “In some cases,” he wrote, “large-scale surveillance with powerful AI, mass propaganda with powerful AI, and certain types of offensive uses of fully autonomous weapons should be considered crimes against humanity.”

The Trump administration doesn’t seem to know what it wants from AI. On one hand, it’s deeply suspicious of certain kinds of models. The White House’s designated AI czar, David Sacks, has criticized Anthropic for “running a sophisticated regulatory capture strategy based on fear-mongering,” essentially accusing the firm of pushing for unnecessary, innovation-squashing limitations and jeopardizing the future of American tech. The administration has also criticized AI bots for sometimes spitting out “woke” replies. On the other hand, Claude is apparently valuable enough that it’s on the cusp of being commandeered by the federal government.

Ball told me that the Department of Defense may have a point—that there’s an argument to be made about reining in Silicon Valley’s control over the government’s use of new technologies. Although the concentration of power among the technocratic elite is certainly troubling, Hegseth’s proposed punishments for Anthropic are misguided and plainly contradictory. The Defense Production Act does allow the government to intervene in domestic industries in the interest of national security (the Biden administration invoked it in a 2023 executive order on AI regulation). But is Claude so important for U.S. national security that the government needs to compel Anthropic to create an untethered new version? Or is it so dangerous that it needs to be shunned—not just by the Pentagon, but by any business connected to the military? A third, even-more-bewildering option is also on the table: Hegseth could decide to simultaneously commission a modified Claude and sanction the company that stewards it.

All of this ignores a much simpler solution: Hegseth could just start a partnership with a different firm. It’s a good time for his department to be in business with tech, since the mood of Silicon Valley has lately become much more Pentagon-friendly. Palantir’s Alex Karp has touted that his software is used “to scare our enemies and, on occasion, kill them”; the technologist and entrepreneur Palmer Luckey is already building autonomous weaponry for the government; and Andreessen Horowitz’s American Dynamism funds are helping funnel the country’s top young minds into defense tech. But rather than look elsewhere, Hegseth is threatening to crush Anthropic—implying that if he can’t control Claude, no one can.

As the defense secretary looks to make an example of the company, he’s taking a cue from Trump, who has used legal and extralegal pressure to effectively force other private businesses, particularly big law firms, banks, and universities, into submission. These acts of coercion have the potential to reshape American capitalism: We are beginning to see a market where winners and losers are decided less by the quality of their products and more by their seeming fealty to the White House. How that will affect the success of businesses and the economy is uncertain.

The Pentagon created this ultimatum precisely because it understands Anthropic’s world-altering potential. The administration just can’t decide if it’s an asset, a liability, or both.

Related:

Here are three new stories from The Atlantic:

- The first couple of a dysfunctional DHS

- Trump’s favorite voter-ID bill would probably backfire.

- Adam Serwer: How America chose not to hold the powerful to account

Today’s News

- A Columbia University student detained this morning by federal immigration agents has been released. The arresting officers reportedly misrepresented themselves as looking for a missing child in order to gain entry to the student’s residential building.

- Hillary Clinton told the House Oversight Committee that she has no new information about Jeffrey Epstein and maintained that she had no knowledge of his crimes; she criticized congressional Republicans’ handling of the probe as partisan. Bill Clinton is scheduled to give his deposition tomorrow.

- Cuban forces killed four people and wounded six after firing on a Florida-registered speedboat that Cuban authorities say entered the country’s waters yesterday and opened fire on a patrol vessel. Cuba claims that the U.S.-based passengers were armed and planning a “terrorist” infiltration.

Dispatches

- Time-Travel Thursdays: Misbehaving dogs in the White House have plagued administration after administration, Nicholas Florko writes.

Explore all of our newsletters here.

More From The Atlantic

- Eliot A. Cohen: The degraded State of the Union

- The tariffs loss is paradoxically a win for Trump.

- Well, that didn’t sound like Casey Means.

- Enough with the bros.

- The Democrats who got weird during the State of the Union

- Radio Atlantic: What the Pentagon fears in Iran

Evening Read

This Looks Like an Insider Bet on Aliens

By Ross Andersen

On Monday night, someone placed a peculiar bet on the prediction market Kalshi. At 7:45 p.m. eastern time, a single trader put down nearly $100,000 on the claim that, by the end of December, the Trump administration will confirm that alien life or technology exists elsewhere in our universe. According to The Atlantic’s review of Kalshi’s trading data, about 35 minutes after this bet was executed, it was followed by another that was almost twice as large (possibly from the same person). These were market-moving events: For one brief stretch, the market appeared to think that there was at least a one-in-three chance that the U.S. government will announce the existence of aliens this year. Perhaps this was just some overexcited UFO diehard with a hunch and money to burn. Or maybe, as some observers quickly noted, it was a trader with inside knowledge.

Culture Break

Explore. When did literature get less dirty? A puritan strain is manifesting in realist novels as a marked absence of straight sex, Lily Meyer writes.

Read. Casey Schwartz on two new books that demonstrate how Martha Gellhorn, Janet Flanner, and other female reporters took journalism in directions that men could not.

Rafaela Jinich contributed to this newsletter.

When you buy a book using a link in this newsletter, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.